I think an onion is the right analogy for healthcare for three reasons: (1) it can make you cry; (2) every time you pull off a layer you learn more; and (3) what you see from the outside is a lot different than what you see from the inside.

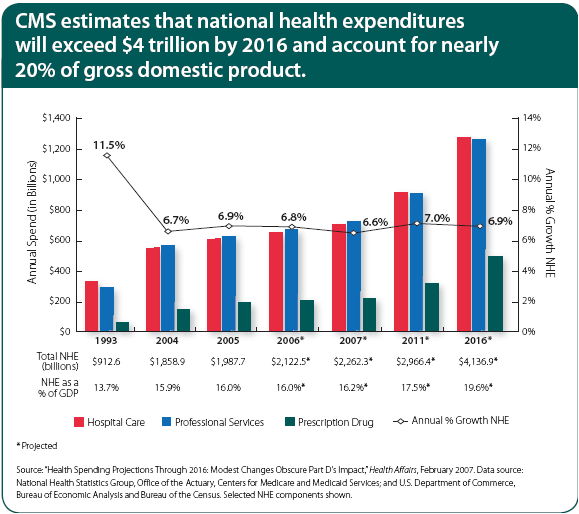

When you have the Congressional Budgeting Office projecting the healthcare costs will be 49% of GDP by 2082, you know things have to change. This is a front page topic almost everyday across the country. But, like an onion, if we don’t handle this right, it will make you cry out of frustration and pain. Change is not easy especially in a complex system that we have today. Finding the right mix of push and pull is going to be important.

When you have the Congressional Budgeting Office projecting the healthcare costs will be 49% of GDP by 2082, you know things have to change. This is a front page topic almost everyday across the country. But, like an onion, if we don’t handle this right, it will make you cry out of frustration and pain. Change is not easy especially in a complex system that we have today. Finding the right mix of push and pull is going to be important.

Quality is still an issue across the system. Biting a bad onion or having a quality issue with your care can make you cry. Look at the USA Today article from the other day about Too Many Prescriptions, Too Few Pharmacies or an entry on my blog about the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

- Every time you pull off a layer you learn more.

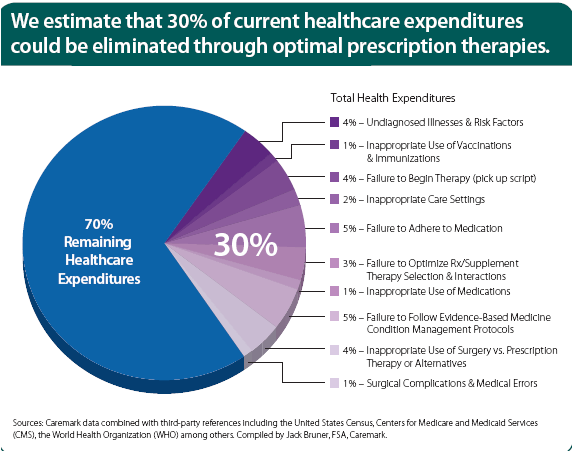

This applies so many ways to healthcare given our system, but I think of this from two perspectives – data / information and process. We have so much data in healthcare, but without the right model to make it into information, it just sits there. And, as we layer data (e.g., medical plus pharmacy plus lab) or integrate healthcare data with demographic data, we can learn so much more about our patients and how to care for them. This ranges from simple questions such as how to motivate behavior (e.g., cost savings versus loss avoidance) to how to deliver information based on their learning style.

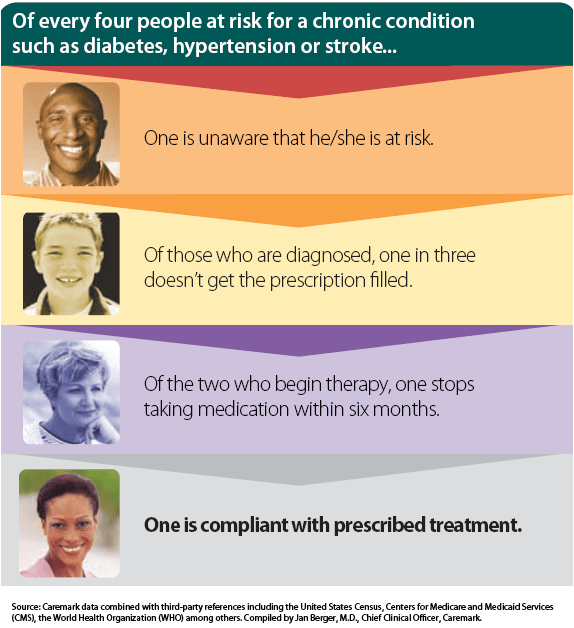

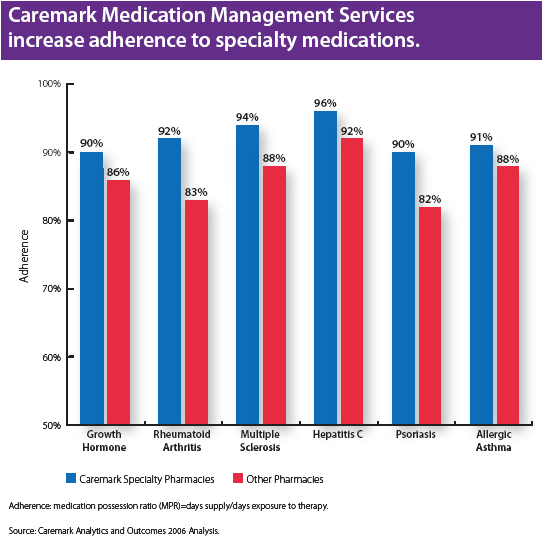

Every question you ask (or layer you pull off) reveals a new set of data that can be transformed into information while at the same time creating new questions. Does the relationship you found in the data simply indicate correlation or is there actual causality there? I look at the data that CVS/Caremark presented around saving 30% of healthcare costs by driving compliance and adherence and wonder why people aren’t jumping up and down trying to capture this savings.

- What you see from the outside is very different than what you see from the inside.

There is a concept in Six Sigma about designing the process from the outside-in. Imagine sitting in the middle of the onion…all you see is onion all around you. That is a common pitfall when solving problems in the industry that we work in. We are too close to the problem and the historical solution. If all we see is the onion, those on the outside (our patients / members / employees) see the onion in relation to other food options. Their expectations for healthcare are produced by other companies that they interact with. They expect web solutions that work. They expect excellent service. They expect to be valued as a customer and of course need the power to walk away and chose another option.

This is a common problem in healthcomm (healthcare communications). We present information in a channel that we believe is effective based on our experience and paradigm (i.e., written, verbal, kinetic). We use language that we think is helpful. A few of my favorite examples from my PBM days are:

This is a common problem in healthcomm (healthcare communications). We present information in a channel that we believe is effective based on our experience and paradigm (i.e., written, verbal, kinetic). We use language that we think is helpful. A few of my favorite examples from my PBM days are:

(1) Telling patients that they need a renewal (prescription). They don’t know what that means. It means they need a new refill since their original prescription refills have run out.

(2) Telling a physician to consider prescribing lisinopril and giving them sample bottles that say lisinopril. [Because, of course, they would know the chemical name for Zestril.]

But, this happens all the time. Telling a person that wants all the facts a lot of qualitative information will fall on deaf ears. Providing a person with lots of options when their looking for an expert opinion will frustrate them. One way to frame this is based on personality type. (Of course, that information isn’t sitting in a database somewhere for us to tap into.)

The reality is that people are different. As you think about your healthcare process, try to be the patient. As one of my bosses used to say, give it to your grandmother and see what she thinks. Can she understand it? Can she make sense of the process?

It’s not easy finding the right amount of onion to use in your recipe, but it is important to continue trying to improve.

February 25, 2008

February 25, 2008